The untold story of WAC Private Byrl Babcock

Byrl Lillian Mitchell was a determined, strong, and independent woman – a single gal, professional, and entrepreneur in an era when it wasn’t exactly fashionable not to marry and settle down in one’s twenties. Born in 1900, Byrl lived in her hometown of Biggs, California, all of her young life. She was the younger of two girls born to Frank and Ida Mitchell. She graduated from high school, then later, from a secretarial school in 1929, at the age of 29. She must have saved her money from her secretarial jobs, because she later became part owner of a jewelry store in Oroville, California, while also working as a buyer for a local stationery store.

In her forties, Byrl met a man named Roy Babcock, who was working as a gardener at her parents’ home in Biggs. Nothing is known about what attracted Byrl to Roy, how long they dated, or if she was excited to finally get married. But in March of 1942, Byrl married 51-year-old Roy Babcock in Yuma, Arizona. She was 42.

For a short time after they wed, Byrl ran a beauty shop in the Gridley Hotel. Roy seemed to take what work he could find, working as a gardener, then as a door-to-door hosiery salesman. Records show that he had Byrl going door to door with him, presumably to give credibility to a man selling mostly women’s products, and perhaps to make his clients feel more at ease with a strange man on the doorstep.

On January 1, 1944, Roy started a new job at a mercantile owned by Mills Orchard Corporation in Hamilton City, outside Sacramento.

A couple of weeks later, on January 14, after just 22 months of marriage, Byrl left Roy and returned home to live with her mother in Biggs. On February 16, 1944, she filed for divorce, citing cruelty. It was her 44th birthday. In the divorce papers, Byrl stated that he “constantly quarreled with her and abused her.”

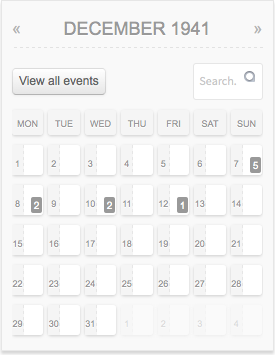

On the national stage, of course, there was a lot going on in 1944. With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, thousands upon thousands of men flocked to enlist in military service, entering the Army, Air Corps, Navy, Marines or Coast Guard. Women – however much they might want to join up – had few such options to serve in their nation’s defense. Some women, with enough training, could join the Army Nurse Corps. Other women found work as civilians in the defense plants springing up all across America.

Despite a growing number of women who wanted to serve in an official capacity, the Army was reluctant to allow women its ranks. Eventually, though, the need for men overseas became too much. After a series of meetings between prominent politicians like Congresswoman Edith Rogers, General George C. Marshall, and others, a bill went to Congress that would allow women to serve in the U.S. Army, freeing up more men to serve on the front lines. The bill passed in 1942. Before the war was over, a hundred and fifty thousand women would serve as members of the Women’s Army Corps, commonly known as WACs.

So here’s our gal Byrl Babcock in 1944, married less than two years, in mid-life, with a violent-tempered husband on her hands. Realizing what Roy Babcock was made of, she didn’t lose any time in getting away from him and forging her own way in the world once again. Nor did she waste a moment wondering what to do next.

Byrl immediately joined the WACs and traveled to Des Moines, Iowa for basic training. She was within one year of the maximum age limit to sign up. She was a spirited and decisive girl, our Byrl. At Fort Des Moines, it is possible that she was assigned to switchboard training, where some of the brightest of the WACs participated. On April 12, 1944, Byrl was set to complete her five-week basic training and graduate as Private Byrl Babcock.

Meanwhile, in Orland, on March 31, 1944, an attorney hired by Roy Babcock filed paperwork for the dismissal of the divorce suit filed against him by Byrl, claiming insufficient proof of the abuse claims. The next day, Roy abandoned his new job at the mercantile without a word, and headed for Des Moines.

Upon arriving in Des Moines, Roy asked Byrl to request a leave so that they could spend time together because he was going “out of the country for several years.” Byrl’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Katherine Ecke, gave her a weekend pass. Later, it was revealed that although passes were not usually given during basic training, Private Babcock was granted the pass because, according to Lieutenant Ecke, “I felt she was an unusually high type person.”

Byrl was due back in training on Monday, April 11th; but she phoned Lieutenant Ecke at 6 a.m. on the Monday to ask if she could stay in town just a few more hours – until 10 a.m. – since her husband was leaving on the 10:30 train, explaining that they had some “legal matters to clear up.”

The couple ordered breakfast at 10 a.m. and answered a call to their room at that time. But when Byrl didn’t appear at noon mess at Fort Des Moines, Lieutenant Ecke became worried.

Lieutenant Ecke phoned the Hotel Kirkwood in Des Moines, where Byrl and Roy were staying. When the couple didn’t answer their telephone, the hotel manager and a bellboy paid a visit to the room. No one answered the door.

Entering the room, the bellman was greeted by an appalling scene: The room was scattered with “four empty whiskey bottles and several coke bottles.” Byrl and Roy were both on the floor, dead from gunshot wounds. According to local coroner A.E. Shaw, Roy had shot Byrl, then himself.

Inside the room, there was a note in an envelope, written by Roy. Addressed, “To whom it may concern,” the note read, “This is the way we wanted it to be. Please bury us together.”

Coroner Shaw also reported that a will, written on stationary from the Kirkwood, dated April 8th, and a letter, dated April 9th, were found in Roy’s pocket. The will was terse, stating only:

To whom it may concern: This is my last will and testament. Being of sound mind when this is written, in the event of my death [sic] any and all money or property is to go without probate to my wife, Byrl L. Babcock.The letter, addressed to “Dear Mrs. Mitchell” (referring to Byrl’s mother, Ida Jane Mitchell), announced that Byrl was planning to divorce him. It further described the troubles between them, stating the cause as “too much family influence,” and that, somehow, his wife had been “forced” to file the divorce paperwork, apparently laying the blame with Byrl’s parents.

Roy concluded the letter by saying that if the divorce paperwork was filed, he would issue a “demurrer”; that is, a complaint that the legal paperwork was legally insufficient to grant a divorce.

Along with the will, the letter, and the note, only a few photos of Byrl and some loose change were found with Roy’s body.

Lieutenant Ecke’s respect, and perhaps fondness, for Byrl are evident through the events that followed. According to the front page article about the murder in the April 11th, 1944 issue of the Des Moines Register, Lieutenant Ecke described Private Byrl Babcock as “one of the finest women in the company.” She personally guarded Byrl’s body on the journey to California, then stood as honor guard to the casket throughout the funeral service, and finally, presented the flag draped over the casket, to Byrl’s mother, Ida Jane Mitchell.

Further, although she was one day short of completing her basic training, Byrl Babcock earned the rank of Private Byrl Babcock, and was buried with full military honors. Her funeral services were well-attended, the funeral home brimming with flowers in her memory.

Byrl Lillian Babcock was buried in the Gridley-Biggs Cemetery in Gridley, California. Her mother, who died on January 2, 1952, is buried there, as well. Ida Mitchell had requested that the Army inscribe Byrl’s headstone with the name “Byrl Mitchell,” leaving off the name of the husband who murdered her. Citing regulations, the Army declined, stating that Byrl had enlisted under her legal name, Babcock; thus, a headstone provided by the Army must show her name as Pvt. Byrl Babcock.

I recently visited the Gridley-Biggs Cemetery and searched for the grave of Byrl Babcock. I was unable to find it, but contacted the caretaker Pat Teague following my visit. I was pleasantly surprised to receive the photo of Byrl’s headstone (above), with the inscription:

Pvt. BYRL J. MITCHELL

W.A.C. Co. 19 Reg. 3

1900 – 1944

As for Roy, his burial place is unknown.

Official reports presume that Roy Babcock may have planned his suicide, but hadn’t originally intended to kill his wife. That presumption seems doubtful, given his violent nature and seeming lack of attachment to any place or person other than Byrl. It’s difficult not to read this story and wish that the leave hadn’t been granted, or that she had returned to her training post first thing Monday morning as scheduled.

Private Byrl Babcock was a courageous woman, of excellent character, well-liked, and successful. It’s impossible to say what great – or ordinary good things – she would have accomplished with the rest of her life. She has no children to carry her on memory, yet her life is worth remembering.

This history is dedicated to “Private Byrl Mitchell,” as she is named on her grave marker, to Lieutenant Katherine G. Ecke, and to the sisterhood of the Women’s Army Corps, with thanks and admiration.

***

Pictured above in the class picture, seated front row, center, is Lt. Katherine G. Ecke, with the graduating class of May 23, 1944. Lt. Ecke must have been very personally affected by Byrl’s death, since she granted the leave, then provided the honor guard to Byrl’s body as she traveled home, and at her funeral. They were both brave and honorable women, and this post is dedicated to their memory.

Also pictured:

Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps recruits at Fort Des Moines, 1942

WACS in switchboard training, Des Moines, Iowa, 1942

WAC recruiting posters

Newspaper clippings from the International

Bill, this is such a meaningful and lovely story and extremely well written. Thank you for caring and for honoring the memory of these brave women.