Guest Blog: “My Longest Day” by Edward C. Oechsli

U.S. Marine Corporal Edward C. Oechsli, penned his story in December 2007. It was submitted to me by Edward’s son, Dennis Oeschsli in June 2015, along with this note:

As is the case with many WWII vets, Dad never talked about the war until he was into his 80’s. At my insistence and nagging, I convinced him to write this down some 10 years ago. Dad is 92 years old and fortunately never suffered any lasting effects of his wounds. He received two Purple Hearts over his tour of duty serving on such garden spots as Okinawa and Peleliu. He ended the war in Hawaii and frequently talks of his recovery and returned to Hawaii several times over his life to look for the old encampment. –Dennis

MY “LONGEST DAY”

by Edward C. Oechsli

May 11, 1945 proved to be my longest day. I found myself with my squad leader, Sergeant Dewey, and my platoon leader, Lieutenant Demler, just below the crest of a ridge in the southern part of Okinawa. We were on the Naha-Shuri-Yonabaru line, the main Japanese defense fortification. This was where they had planned to make their stand, to defend the island at all costs. However, at that time, I did not know what day it was, or where I was on Okinawa. The day started as usual. I woke up in a foxhole that I had dug the evening before, with Pat Jennings. He and I would alternate on sentry duty. He would watch for two hours and wake me and I would watch for two hours. So we each got a half-night’s sleep each night, on an ideal night. Then we crawled out of our hole and splashed some water on our faces, if we had any. Water, that is. Then maybe energy bar for breakfast, and coffee, if we had any.

The army had been stopped for some time at this point, due to fierce Japanese resistance. We were to push through their lines and move up front and begin a frontal assault to end the stalemate. We moved up the hill, after pushing through the Army positions. The hill was stripped of everything living, only disturbed earth, large rocks, and three Marines were there now near the crest.

Lt. Demler was on his walkie-talkie getting orders from the command in the rear. Then he took about five steps to the very crest of the ridge for a better view of what was ahead. Almost immediately he fell to the ground. I saw blood pouring from his mouth.

“Let’s get him down here out of the line of fire. Get my poncho,” Sgt. Dewey said.

So I crawled next to him and pulled his poncho from the straps on his backpack. Then we crawled up to the lieutenant and unfolded the poncho beside him, all the while keeping as flat to the ground as we could. Then we carefully pulled Lt. Demler over on the poncho. We scooted on our stomachs back down from the very crest of the hill. We’d scoot a foot or two and then we would reach up and grasp the poncho to drag it down to our position. We repeated this until we had reached a spot we thought was out of the line of fire.

We tried to give aid to the lieutenant. We saw a projectile had gone through his cheek, striking his teeth and tongue and blowing it all out through the opposite side of his face. He was still conscious and I watched him as he wrote with his finger, “MEDIC.”

Of course we were already trying to get one of our two corpsmen. Dewey was trying on the walkie-talkie and I was yelling down the hill calling for Wayne. Finally, someone yelled back, “Wayne has been hit!”

Finally Dewey got someone on the phone and asked to have Yak come up. He was our other corpsman.

“He’s been killed,” was the reply. So Dewey asked for stretcher bearers. Once again Lt. Demler wrote “MEDIC” on the ground with his finger.

Finally stretcher bearers arrived. I helped put the lieutenant on the stretcher and they carefully made their way back down among the rocks, boulders, and shell craters, trying to maintain their balance as they headed back to an aid station.

We were told on the walkie-talkie to maintain our positions. I was the corporal in charge of the first group, in the first squad, in the first platoon, of “A” Company. There was no one in front of me.

Soon our company commander, Captain Romo, came forward to take over Lt. Demler’s duties. He told me to go over the crest of the ridge where the lieutenant had just been shot and advance forward. I asked how far I should go. The Captain replied, “As far as you can.”

I had no idea what was over that ridge but I would be the one to find out. So I got to my feet and started running. I went over the top of the ridge and maybe ten feet down the other side where it flattened out somewhat on top. I ran forward on this ledge and asked myself, what do you do now? I have no idea how far or for how long I ran.

Suddenly I was hit by something that felt like a run-away freight train. It was hot and it knocked my legs out from under me. I flew through the air and hit the ground heavily. I realized immediately that I had lost my rifle.

As I hit the ground I knew I was on a hillside. I helped myself roll over maybe three times down the hill and stopped myself in a slight depression in the earth. I took notice of my circumstances. Already the whole left leg of my dungarees was soaked with blood from just below my hip down past my knee. I was fortunate in that that the only thing I lost was my rifle. I still had my ammo belt with my first aid kit fastened on the back side of it. And I still had my knife fastened in its scabbard.

I removed both my ammo belt and my knife from the scabbard. I slit my dungarees from my hip all the way down through the ankle seam. I checked my wound and saw I had been shot high in my thigh about two and one-half inches below my crotch level. It had entered directly in the front center of my thigh and exited directly in the center of the rear of my thigh

I opened my first aid kit and got out a package of powdered sulfa and sprinkled it on the wounds, front and rear. I found the largest bandage in the kit and wrapped it tightly around my thigh. It had its own ties on it so I wrapped them around my thigh and tied them very snugly. Then I located the “wound tablet” in my kit and got my canteen of water and took this pill. All this was done just as I had been taught in boot camp.

So, now, what comes next? Here I am, all alone, lying on the side of a hill maybe 200-300 feet out in front of our lines, wounded, without my rifle, very close to the Japanese lines and no one seems to be moving. I figure I am out of sight of the enemy as I did not draw any fire while I doctored my wounds. And I am out of sight of my fellow Marines as I saw no one come past me and I am down over the side of a hill.

My only defense is two hand grenades I had in my dungaree pockets so I get them out. I loosened the pins in each one and pulled the pins partly out to quicken my response time. I also decided that if the enemy came I would pull the pin, let the spoon fly free, then count to three before throwing them. This way, I figured the grenades will explode almost immediately and they will have no time to avoid them or throw them back at me. Then I put my knife in easy reach. I told myself I had done all I could do so now I would just have to wait and see who would find me first—Japanese or American.

But it did not prove to be that simple. Suddenly I heard a tremendous explosion—then another and another. Perhaps a half dozen, one following the other. They seemed to come from behind me. Then a pause followed by another group of explosions. These seemed to be closer. Then the third group of explosions. These sent chills down my spine. They were directly behind me and most of the group exploded to my left and one to my right.They shook the earth as the shells dug in, ripped large craters in the land with a screeching, squealing sound. They seemed to be ripping the very heart and soul out of the earth. I knew what the awful sound was as I had experienced it before. It was the large mortars seeking the range they wanted and moving bit by bit ahead with each barrage. The next barrage would be decisive for me. Where would they land?

I immediately remembered a similar assault I had laid through before. In that one, a PFC who was about twenty yards to my left, was fearful the next barrage would get him so he jumped up and started running. A shell exploded about twenty feet from him and the shrapnel killed him instantly.

Because of this I did not run that time and could not run this time even if I was so inclined—which I was not. I just gripped the ground a little tighter, if that was possible.

The next barrage hit, wrenching the earth around me and showering me with dirt like a large hail storm. I knew I had made that one and that the next one would be safely out in front of me. This was what they call “friendly fire” today. Then it was “Don’t those bastards know where they are shooting?”

On the second barrage after that, they had their range, as I could hear a great concentration of fire that went on and on for an extended period of time. Then it ceased and all was quiet. I lay there in my position wondering what would happen next. There was not much daylight left. I did not have a watch and have no idea how many hours I had been out there. In World War I this was called “no-man’s land” between your line and the enemy’s line.

But I had done my job. I had gone out in no-man’s land and drawn enemy fire. Our observers had seen where the fire was coming from and brought heavy fire to this area. Later, as I lay there, I heard a voice I immediately recognized as that of Herbert Withrow from my company. “Anybody else out here?” I answered instantly,” Withrow told me.

They carried me on a stretcher, struggling over very rough terrain that was potted with craters, some made today and others perhaps by naval bombardment, aircraft, or artillery fire from days or weeks past.

I was taken to a temporary first aid station. A medic checked me out and said, “Great, I don’t have to touch you. You did a better job than I can do. You’re good to go.”

So my stretcher was hung to a MASH unit. It was dark when I got there and I was surprised to see their tents were well-lighted so close to a combat zone. I was placed on an “operating table” and the doctor started removing my bandage.

“You did this?” he asked.

“Had to, “ I said.

“You saved your life. With this wound you would have bled to death in just a couple minutes but what you did stopped the bleeding almost immediately.”

The doctor said, “ This type of wound is very slow healing because it has to heal from the inside out. I am going to pack it from both the front and the rear with this treated gauze strip. I will first leave a tab sticking out and then fill the wound from the center of your leg out, doing this on front and back. Then the hospital will pull this tab out a little, giving it time to heal in the center. At regular intervals, they will repeat this until finally the outside end of the gauze will be pulled free.”

That doctor really impressed me with his interest and concern. Then I was carried into another tent and placed on a cot for the night and my “longest day” was over.

Afterthoughts

- If Withrow had not thought to yell “anybody else out here?” and had left after searching the area as they had been doing, what would have been my outcome? At the least I would have spent a horrible night out there.

- I wonder if my friend Humenick was killed by “friendly fire” as I could have been.

- Months after I had been discharged my sea bag was delivered to me in Louisville. I opened it and retrieved Humenick’s sea bag from within my own bag. It included his mother’s and also his brother’s addresses. It also contained a fancy knife his brother had made for him and other odds and ends. I packed all his stuff and sent it to his brother. He and his mother wrote me wanting any information I could give them and told me if I was ever in Minneapolis, I would be a welcome guest in their home.

- Many years after the war I learned that there were monthly rosters kept of each battalion during the war. I got one for May 1945 showing who was there. Of our company or approximately 250 men, 24 were killed and 111 wounded during May—54% casualties and most of them on May 11, 1945.

- The location of the entry and exit wound shows that I was running directly at the one who shot me. I wonder how close I was to him. Maybe just a few feet.

- The bullet that hit me had a metal jacket, perhaps a metal piercing bullet. So it left a hole in the rear of my leg just very slightly larger than the front. Some bullets splatter out and tear a big chunk out as they go through.

- What if I had lain where I fell instead of rolling down the hill a few feet?

- And maybe worst of all, what if I had used my first aid kit on something else as some guys had done?

- I was flown to Guam and as I would require extensive hospital time, on the third day I was flown to Hawaii. The flight to Guam was my first ever flight. I was on a stretcher hanging from the wall. At Hawaii I had just been released from rehab when the war ended.

Bill Beigel’s note:

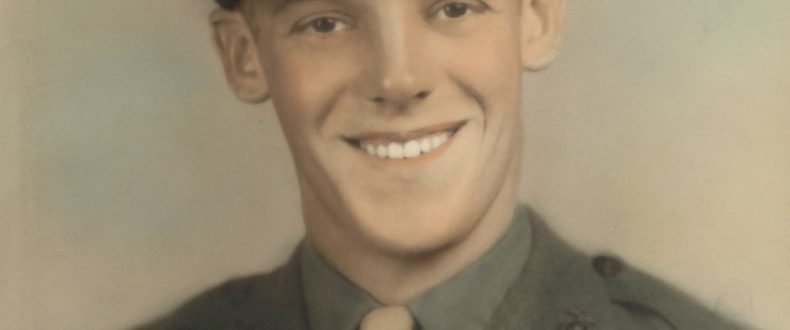

Corporal Edward C. Oechsli served with 1st Squad, 1st Platoon Company A with the U.S. Marines in World War 2.

In the six months that he served in and Asiatic-Pacific Area in WW2, Douglas Demler, Jr. received the Silver Star, the Purple Heart, the Presidential Unit Citation with ribbon Bar and one Star, the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-pacific Campaign Medal, and Victory Medal World War II. I researched 2nd LT Douglas Demler prior to receiving this submission from Dennis Oechsli. Please check back for a blog post dedicated to 2nd LT Douglas Demler.

Pictured: USMC Corporal Edward C. Oechsli; 2nd LT Douglas Demler; excerpts from Demler’s IDPF (Individual Deceased Personnel File).

Ask Bill or comment on this story